“How do you feel about meetings at work?”

“They’re amazing, absolutely stunning. Incredibly productive, deeply satisfying and always a great use of time. I love ‘em, can’t wait for the next one!”

Okay, so the above conversation didn’t really take place. However, a quick search on the internet will produce a plethora of statistics and information regarding the ugly truth about meetings. Here’s just a few of them:

- Middle managers spend over 38% of their time in meetings

- Senior managers spend over 50% of their time in meetings

- Meetings are unproductive – so say 67% of executives

- 18% of an organizations collective time is spent in meetings (apparently, this figure has grown each year for the past 9 years)

The above are just random examples gleaned from a quick search but I do believe they are representative of the staggering waste of time, money and resources that is the result of unproductive, poorly managed meetings. This is most certainly reinforced by the frequent comments of clients, colleagues, friends and family.

Assuming we ‘need’ a meeting (the first rule of effective meetings being don’t have one unless it is necessary) why are they so often deemed as an unproductive waste of time, money and resources? Why are they so often characterized by frustration and dissatisfaction?

In my 25 years of researching and growing my understanding of individual and group thinking productivity, I have identified two fundamental elements that make the difference between success and failure. Perhaps somewhat obviously, these are 1. behaviors and 2. processes.

- Behaviours

The behavioral aspect of thinking falls into two camps, internal and external. The internal behaviors are concerned with what goes on in our own minds and are principally (but not exclusively) about focus and discipline. The external behaviors are those things that we have been historically exposed to or are currently exposed to that have an adverse impact on individual and group thinking productivity. Manifistation of this commonly includes (amongst many others):

- Cynicism

- Over dominance

- Ridicule

- Too much debate/argument/discussion

- Lack of individual contribution

It is largely about the negative interactions that adversely effect thinking efficiency, productivity and motivation.

- Processes

The second fundamental element is concerned with the individual and group thinking processes that are applied and adhered to during meetings. There are a great number of proven systematic thinking tools and processes that can be applied to a variety of situations that will ensure high levels of productivity and successful outcomes. The applications include (again amongst many others):

- Setting a clear and appropriate focus

- Problem definition

- Idea/concept generation

- Value engineering

- Cost reduction

- Process improvement

- Problem solving (including difficult and/or highly technical problems)

- Selection and prioritization

- Decision making

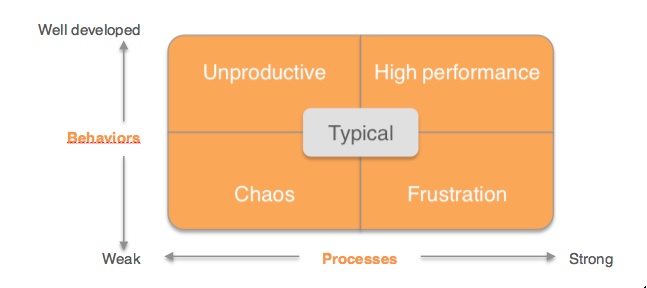

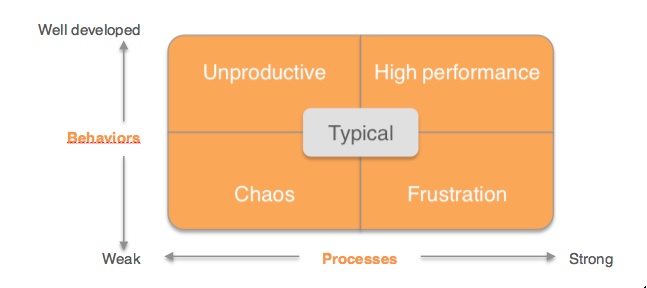

It is by combining the right behaviors with effective processes that we can conduct highly productive, efficient and satisfying meetings. Weakness in any area will lead to problems, as the following model illustrates.

It is possible to identify from the Behaviors + Processes Matrix why our meetings might be a struggle and zapping valuable time and resources (and adversely affecting employee motivation). The segments can be explained as follows.

Chaos (weak behaviors and weak processes)

The chaotic segment is where the individual and group behaviors and processes are weak. In the extreme, there is anarchy!

Chaos is often characterized by some, if not all, of the following:

- Argument

- Debate

- Many voices (free for all) or one voice (domination)

- Interrupting

- Unproductive

- Lack of contribution

- Waste of time

- Personal attacks

- Hidden agendas

- Ridicule

- Unstructured

- Lack of focus

- Despair

Frustration (weak behaviors and strong processes)

Frustration is often born out of having a good understanding of thinking processes and tools but where the behaviors are still weak and preventing groups from getting on and applying what they know to be good sense.

Frustration is characterized pretty much the same as chaos.

Unproductive (well developed behaviors but weak processes)

The unproductive segment applies when the individual and group behaviors are well developed but the processes are weak. Consequently, the group is likely to work well together and have a nice ‘feel’. However, there are low levels of productivity driven by a lack of effective thinking tools and processes. This can also lead to frustration due to a lack of productivity and results.

The unproductive segment is characterized by:

- Good listening

- Not interrupting

- Willingness to contribute

- Being well prepared

- Discussion

- Justification

- Debate

High performance (well developed behaviors and strong processes)

High performance is achieved through well-developed behaviors and the application of strong processes.

High performance is characterized by:

- High levels of productivity

- High quality output

- High levels of satisfaction

- Quality decisions

- Everyone contributing

- Great results

Occupying the middle ground is perhaps what could be considered as typical meetings. This is where some of the behaviors are constructive but there is still evidence of counter productive behaviors and where there is the application of some constructive thinking processes. In my experience, these types of meetings are fairly common but they do leave room for significant improvement and raised levels of productivity.

Typical meetings are often considered ‘good’ meetings, which is a shame and somewhat symbolic of the endemic culture.

Meetings seem to have become an embedded part of our business culture. The comments I frequently hear most certainly point to them being a huge drain on resources and often a significant barrier to people getting on with their day jobs. If meetings are necessary and we are to spend a significant proportion of our working lives attending them then perhaps considerably more emphasis should be placed upon making them more efficient, productive, satisfying and enjoyable.

If you decide to improve your meetings I very much hope the above will provide you with some understanding of where your efforts may be best placed.

About the author:– Tim Rusling runs Problem Engineering + Behavioral Science, a consultancy and training organization with a focus on making thinking as productive as possible. He works with organizations helping them to unleash the thinking capability of their employees. Working globally, he has helped clients generate high volumes of ideas and concepts, solve the toughest of problems and innovate. He is author of the book ‘Systematic Innovation’.

Contact details:

www.problem-engineering.com

tim@problem-engineering.com

t. +44 (0)7901 910645